Building Cooler Neighbourhoods:

The Case for Corridors in India

Tarun Garg and Akhil Singhal

1. It’s Time to Build Heat Resilience at the Neighbourhood Scale

India’s cities are experiencing increasing heat stress, with urban areas warming nearly twice as quickly as rural areas and regularly reaching 50°C.1 This is a significant issue that disrupts daily life, reduces productivity, and increases mortality. While national and state-level efforts like Heat Action Plans (HAPs) and the India Cooling Action Plan (ICAP) are helping cities prepare and respond, most current interventions still emphasise short-term response or focus on active cooling technologies.2

In this brief, we introduce an emerging and flexible neighbourhood-scale strategy called “cool corridors” that layers nature-based solutions and passive cooling strategies in new and existing urban public spaces. As India faces increasing demand for equitable, climate-friendly interventions, cool corridors can complement existing efforts by addressing outdoor heat in the spaces where people travel, work, shop, and spend leisure time.

Recent efforts across the country indicate growing interest in strategies that align well with the cool corridor approach. Telangana’s comprehensive cool roof policy, Tamil Nadu and Maharashtra’s urban greening initiatives, and newer HAPs that broaden past short-term response are all pointing to an emphasis on long-term heat mitigation.3 With only 8%–10% of India’s households having access to air conditioning, neighbourhood-scale cooling strategies like cool corridors offer a promising path to urban heat resilience.4

2. Making the Case for Cool Corridors

Defining cool corridors

Although not yet formally defined, cool corridors refer to a strategy for layering and networking multiple cooling interventions together to form heat-resilient corridors through a neighbourhood’s most heat-vulnerable, highly trafficked locations.5 Because urban heat is driven by a complex set of factors and experienced inequitably within neighbourhoods, this strategy provides a multifaceted response tailored to the community it will serve.

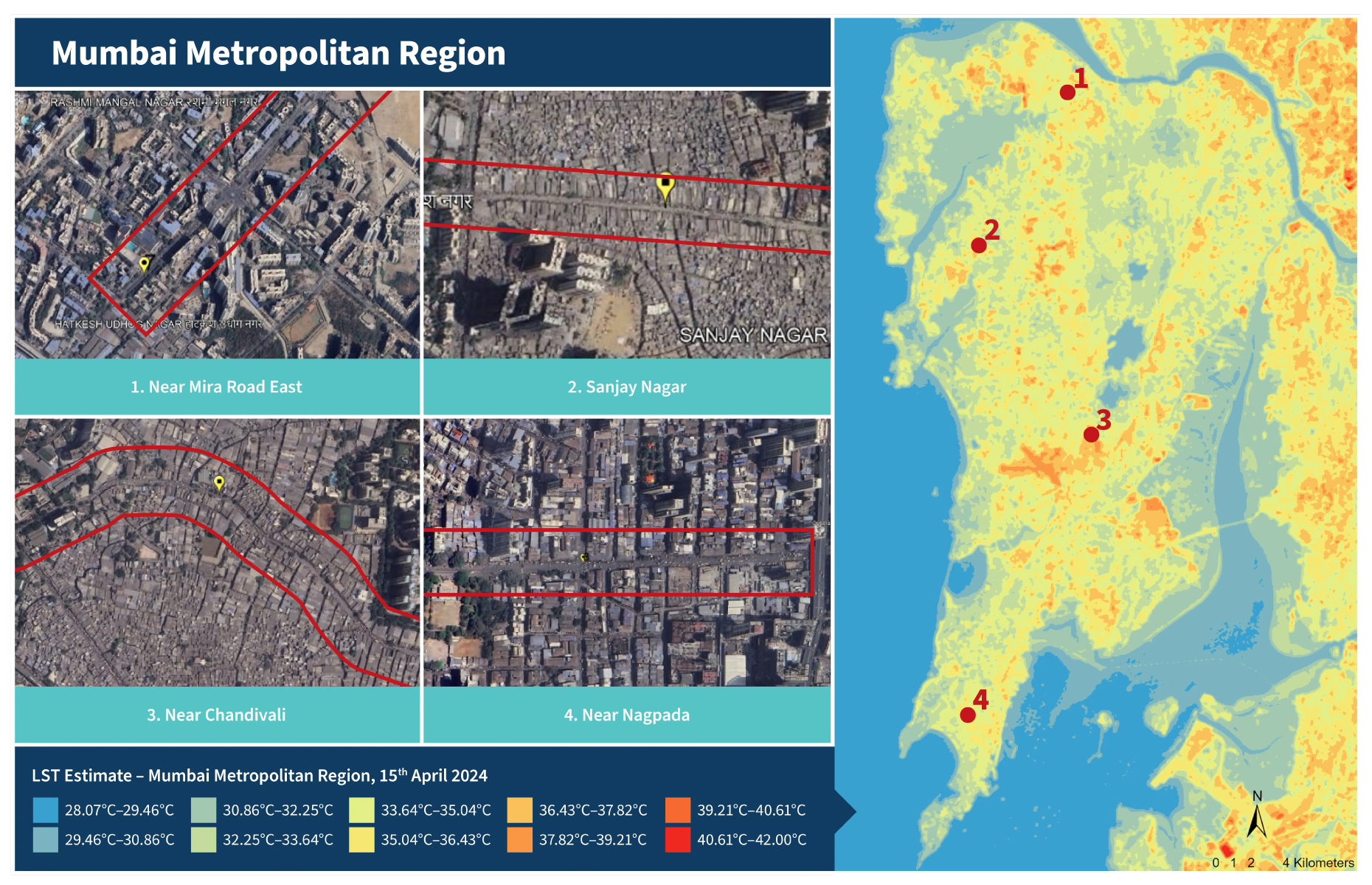

Exhibit 1: Illustrating the Elements and Function of a Cool Corridor

Source: RMI Graphic

Source: RMI Graphic

The cool corridor concept is gaining momentum in the United States, where a diverse range of cities and states are at relatively early stages of proposing, implementing, and evaluating related projects and policies. The locations include Phoenix, Arizona; Tampa, Florida; Bridgeport, Connecticut; Portland, Oregon; New York City; Washington, DC; and Massachusetts.6 Internationally, several countries (including Singapore, Japan, Colombia, and parts of the EU) have pioneered similar neighbourhood-scale cooling initiatives largely focused on urban greening.7

Elements of cool corridors

Cool corridors can draw from a wide array of cooling interventions, which should ultimately be tailored to the local context. These interventions can be organised into three broad categories that reflect the key strategies for addressing urban heat.

- Nature-based solutions: This category of solutions leverages natural ecosystems to address societal challenges with dual benefits to both human health and well-being and the environment.8 In urban landscapes, natural features are often described as green infrastructure (greenery such as trees, urban forests, and green facades like walls and roofs), blue infrastructure (water bodies such as ponds, streams, and reservoirs), or mixed blue-green infrastructure (including rain gardens, wetlands, and mangroves). In India’s dense and rapidly growing cities, protecting existing natural features will be a critical lever for reducing heat at the urban scale, with co-benefits for air quality and beyond.9

- Passive cooling measures: These measures manage heat either by preventing it from entering spaces in the first place, absorbing and releasing heat to regulate temperatures, or removing excess heat without the support of active cooling systems.10 Unlike nature-based solutions, these measures primarily rely on the design elements and material choices. A common measure is creating pavement with highly reflective coatings or other light-coloured materials that reflect solar radiation, absorb less heat, and reduce cooling energy demand.11 Additional passive measures include shading, permeable pavements that enable evaporative cooling, natural ventilation, optimised building orientation, and the use of thermal mass to moderate temperature fluctuations.12

- Neighbourhood heat safety measures: There are additional “safety net” measures that cities may incorporate into cool corridors in the short term to protect residents during extreme heat events. Examples include response measures like heat wave warning systems, public cooling centres, and water stations. Installation of other localised cooling solutions, such as evaporative cooling structures, misting systems, and fans, can also provide relief, though effectiveness declines as humidity increases.13

Research has demonstrated that individual cooling interventions can deliver measurable but geographically localised reductions in urban temperatures. For example, a cool roof pilot in Chennai reduced roof surface temperatures by 9–12°C and indoor room temperatures by 0.5–2°C, and a bus stop misting system in Ahmedabad reduced temperatures by 6–7°C.14 Internationally, green corridors in Colombia have helped reduce average city temperatures by 2°C.15 The combined cooling impact of multiple interventions is less well understood, but there could be an amplification of benefits.

India’s opportunity to adopt cool corridors

Cool corridors are a compelling strategy for cities aspiring for long-term heat resilience. Four key factors make them well-suited for widespread adoption in India:

- Adaptable: Cool corridors can be implemented across a wide range of urban contexts and should be tailored to reflect local climate, geography, urban design, and community needs. In existing neighbourhoods, cooling interventions can be integrated into the urban fabric of buildings, streets, and public spaces without requiring large-scale redevelopment. Retrofit efforts can be guided by space availability and economic feasibility. In newly developing areas, they can be planned and incorporated from the beginning, giving developers more flexibility to leverage natural features such as ecological corridors and wind flow patterns.

- Efficient: Cool corridors can be a cost- and resource-efficient strategy for urban heat mitigation. By targeting the most heat-stressed areas (such as those with limited green cover, concentrated affordable housing, or proximity to schools and community hubs), cities can maximise benefits while minimising investment. In rapidly densifying areas where space is limited and large-scale nature-based solutions like parks or forests are difficult to implement, cool corridors offer a practical alternative. Their ability to leverage existing infrastructure helps reduce the need for land and large capital works.

- Implementation-ready: Cool corridors have strong potential to align with India’s existing policies, planning frameworks, and funding streams, but this will require deliberate coordination. This intersectional strategy may attract support from a range of funding sources, including government and philanthropic investment in health, urban greening, infrastructure, transportation, and beyond. Integrating cool corridors into existing heat resilience and urban development planning and policy can clarify governance structures and make it easier to implement, maintain, and scale projects.

- Measurable: Monitoring the impact of cool corridors on temperature and other outcomes like quality of life, health, and productivity will build the evidence base for this strategy.

Quantification of the geographic and demographic extent of benefits will also be valuable. Ongoing evaluation and reporting will improve transparency and accountability, build public trust, and enable data-driven improvements.

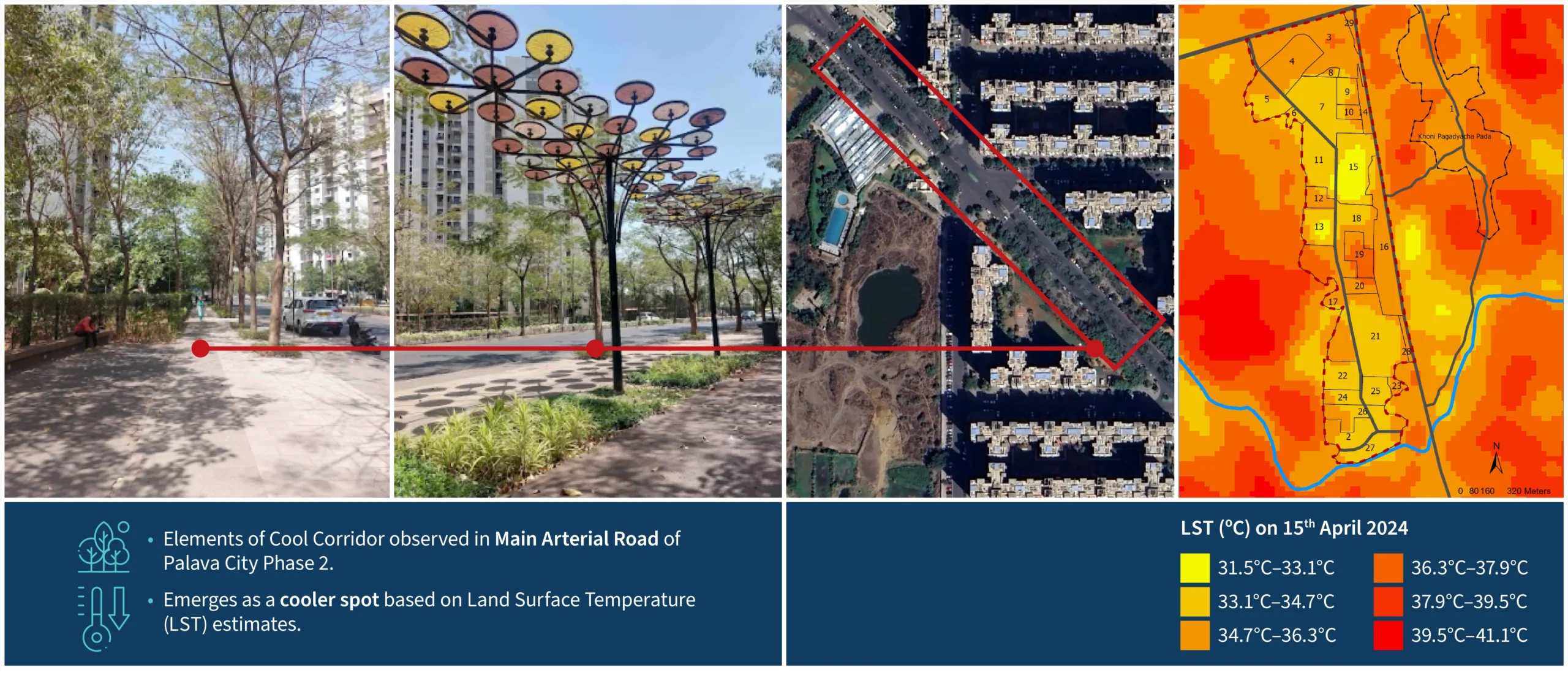

Exhibit 2: Visualising an Early Success Story in Palava City

Palava City

Source: RMI Graphic

Source: RMI Graphic

Since 2018, RMI India has been a collaborator in sustainability planning for Lodha’s Palava City, a notable development designed with features to promote heat resilience.16 Thanks to this familiarity with the site, we identified an existing main road that features many of the defining elements of a cool corridor, despite not being intentionally designed as one. As shown in satellite imagery and site photographs, this road is lined with trees and incorporates additional landscaping. Shade is provided by adjacent high-rise buildings and installed shade structures, and the street channels breezes between buildings. The map of land surface temperatures also confirms that this road’s immediate surroundings are relatively cooler than much of the broader vicinity. Lodha estimates that Palava consistently achieves land surface temperature reductions of around 2°C, with localised reductions of up to 7–11°C in vegetated and shaded areas.17

3. Planning for and Scaling Cool Corridors

Proposing a flexible six-step process

We propose a six-step process for identifying candidate locations for future cool corridor development — simple enough to be adapted locally but structured enough to support scaling this concept. While it is recommended to follow a data-driven approach throughout, final selections may involve some subjectivity in identifying the most suitable locations.

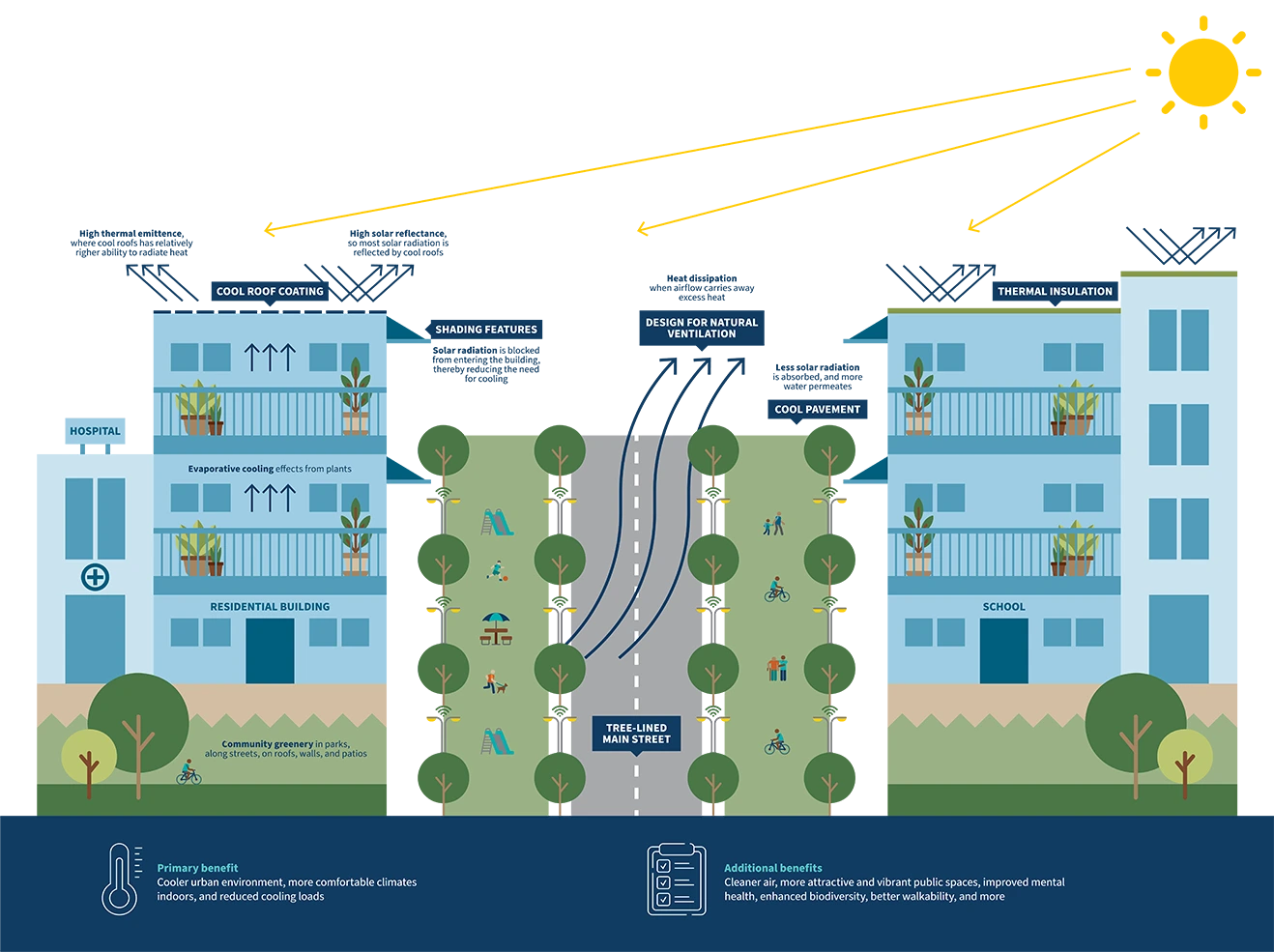

- Investigate heat conditions using land surface temperature (LST) data or other urban heat mapping methods to identify hot spots experiencing elevated heat stress. While LST is a useful proxy, taking local temperature measurements can supplement and ground truth.

- Prioritise highly vulnerable locations within those hot spots, such as informal settlements or pedestrian zones, where individuals face disproportionate exposure.

- Identify physical opportunities by assessing neighbourhood road infrastructure, like local and collector roads, which could serve as the backbone for cool corridor transformation.

- Evaluate feasibility and impact for each of the candidate locations by considering the site’s unique barriers, enabling factors, funding opportunities, and community priorities like proximity to schools, healthcare facilities, and transit nodes. This step can also consider how different combinations of interventions might perform, which could be supported by simulation tools or scenario modelling.

- Design a corridor plan in which selected interventions are tailored to local conditions and responsive to the area’s built form, climate, population needs, and implementation constraints. Implementation may be phased.

- Scale individual corridors by interconnecting additional corridors over time to form a broader network that links neighbourhoods and integrates with existing natural infrastructure like parks, water bodies, or ecological corridors.

Demonstrating the process in practice

Building on the promising findings in Palava, we selected the broader Mumbai Metropolitan Region and the National Capital Territory of Delhi as initial test beds and applied the first three steps of the process as an initial demonstration. Using a low-cost, accessible heat-assessment approach based solely on open-source data,18 Exhibit 3 identifies nine candidate locations for cool corridors across selected neighbourhoods in Mumbai and Delhi.

Exhibit 3: Assessing Future Opportunities Across Mumbai and Delhi

Source: RMI Graphic

Navigating barriers and enabling factors

The demonstration above focuses on the first three steps of the proposed process and intentionally pauses before step four — assessing feasibility — because this step is highly context-dependent and carries significant implications for implementation decisions. Evaluating a candidate site’s barriers to implementation and enabling factors requires a nuanced understanding of local conditions, including governance structures, land use patterns, and community dynamics. Because these factors vary significantly across India’s states, cities, and neighbourhoods, they must be surfaced through place-based engagement. That said, several categories of barriers and enablers are likely to shape the feasibility of cool corridors.

- Physical factors: Limited land availability, narrow rights-of-way along road infrastructure, and road encroachments can restrict the space needed for interventions. Physical infrastructure, like overhead and underground utilities, may also limit where interventions can be installed. On the other hand, existing footpaths, wider roads with good connectivity, and undeveloped/underused plots can support corridor design.

- Institutional factors: Unclear land ownership and fragmented coordination across municipal departments can slow progress in creating corridors. Cool corridors are more feasible where there is clear jurisdiction, interdepartmental coordination, and integration of NbS with city-wide master plans, policies, and missions.

- Social factors: A key challenge in fostering community involvement in neighbourhood development is the lack of awareness about the tangible benefits of these interventions. To address this, community awareness campaigns and real-world case studies can be powerful tools to demonstrate how such initiatives can improve quality of life. The success of these efforts depends on enabling factors such as trusted local leaders and clear, consistent messaging that builds trust and support.

- Operational factors: Urban local bodies often face constraints such as limited staffing, technical expertise, maintenance capacity, and gaps in funding or incentives, which can hinder the implementation of initiatives like cool corridors. However, significant opportunities can emerge when these projects are aligned with ongoing or planned capital works, tap into existing funding schemes, or are supported by strong partners.

Recognising and addressing these conditions early, before committing to sites, is essential to ensuring that cool corridors are locally viable and ready for implementation.

4. The Path Forward

To support meaningful implementation of cool corridors, we propose a phased “Think-Do-Scale” framework. This brief serves as a foundational thought leadership piece in the “Think” phase, with substantial opportunities for further action in the “Do” and “Scale” phases.

Exhibit 4: Deploying Cool Corridors at Scale

| Think | Do | Scale | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Objective | Research, raise awareness, generate dialogue, and build alignment with stakeholders across multiple sectors around a shared vision for heat resilience through cool corridors. | Translate thought leadership into targeted pilots and local demonstration projects to test, refine, and evaluate the cool corridor strategy in real-world settings. These early projects serve as proof points to lower risk of adoption and enable scalability. | Widespread and strategic integration of cool corridors into policy for long-term heat mitigation. Leveraging existing planning and funding mechanisms will also provide a strong foundation for scaling up cool corridor implementation. |

| Timeline | Near-term | Medium-term | Long-term |

| Priority Stakeholders | State and city governments, urban planners, real estate developers, NGOs, and community-based organizations | Local governments (city and urban local bodies), real estate developers, financing institutions, NGOs, community-based organizations, and solution providers | Government (local, state, national), real estate developers, and financing institutions |

Source: RMI

Cool corridors represent a timely and complementary addition to India’s growing toolkit for addressing extreme heat. The concept’s greatest strength is its intentional flexibility, serving as a framework that cities can adapt to their own context and enabling tailored combinations of cooling and safety interventions in the areas that need them most. As heat risk continues to grow, cities across India will benefit from exploring innovative and integrated strategies like this to protect people and sustain livable communities that are resilient and prepared for the future.

5. Endnotes

1. Fahad Shah, “Urbanization Is Intensifying India’s Summer Heat and Rain,” Time, July 7, 2025, https://time.com/7300435/india-urbanization-climate-impacts-heat-monsoons/</>, “New Delhi records highest-ever temperature of 52.3C as north India swelters,” Al Jazeera, May 29, 2024, https://www.aljazeera.com/gallery/2024/5/29/photos-north-india-swelters-as-new-delhi-records-highest-ever-temperature-of-49-9c; “Delhi ‘unbearable’ as temperatures near 50C,” BBC, May 29, 2024, https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/c166xxd4y36o.

2. Aditya Valiathan Pillai, “Guest post: The gaps in India’s ‘heat action plans,’” CarbonBrief, March 28, 2023, https://www.carbonbrief.org/guest-post-the-gaps-in-indias-heat-action-plans; Aditya Valiathan Pillai and Tamanna Dalal, How Is India Adapting to Heatwaves?: An Assessment of Heat Action Plans With Insights for Transformative Climate Action, Centre for Policy Research, 2023, https://cprindia.org/briefsreports/how-is-india-adapting-to-heatwaves-an-assessment-of-heat-action-plans-with-insights-for-transformative-climate-action/; Expanding Heat Resilience Across India: Heat Action Plan Highlights 2022, NRDC, 2022, https://www.nrdc.org/sites/default/files/india-heat-resilience-20220406.pdf; India Cooling Action Plan, Ozone Cell, Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change, Government of India, 2019, https://ozonecell.nic.in/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/INDIA-COOLING-ACTION-PLAN-e-circulation-version080319.pdf.

3. Telangana Cool Roof Policy 2023-2028, Municipal Administration & Urban Development Department, Government of Telangana, 2023, https://telangana.gov.in/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/Telangana-Cool-Roof-Policy-2023-2028.pdf; Prima Madan et al., “Telangana Announces a Groundbreaking Cool Roof Policy,” NRDC, April 3, 2023, https://www.nrdc.org/bio/prima-madan/telangana-announces-groundbreaking-cool-roof-policy; Beating The Heat: Tamil Nadu Heat Mitigation Strategy, Tamil Nadu State Planning Commission, 2024, https://spc.tn.gov.in/wp-content/uploads/Heat_Mitigation_Strategy.pdf; Greening Mumbai: Citizen’s Handbook For Greening Initiatives From Balcony Gardens To Large Scale Plots, Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation, 2023, https://portal.mcgm.gov.in/irj/go/km/docs/documents/HomePage%20Data/Related%20Links/GREENING%20MUMBAI-Citizen’s%20handbook%20for%20greening%20initiatives.pdf; How Is India Adapting to Heatwaves?, 2023.

4. Hanna Ellis-Petersen, “‘A matter of survival’: India’s unstoppable need for air conditioners” Guardian, December 5, 2023, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2023/dec/05/india-unstoppable-need-air-conditioners.

5. “Cool corridors,” Heat Action Platform, Adrienne Arsht-Rockefeller Foundation Resilience Center, accessed March 17, 2025, https://heatactionplatform.onebillionresilient.org/heatactionpolicy/cool-corridors-commitment/.

6. “Cool Corridors Program,” City of Phoenix, accessed March 17, 2025, https://www.phoenix.gov/administration/departments/streets/initiatives/cool-corridors.html; Shade Phoenix: An Action Plan for Trees and Built Shade, City of Phoenix, 2024, https://www.phoenix.gov/content/dam/phoenix/heatsite/documents/BP_ShadePhoenixPlan_Report_031025_EN.pdf; Cool Neighborhoods NYC: A Comprehensive Approach to Keep Communities Safe in Extreme Heat, The City of New York, 2017, https://www.nyc.gov/assets/orr/pdf/Cool_Neighborhoods_NYC_Report.pdf; “Apply to the Cool Corridors Grant Program,” Commonwealth of Massachusetts, accessed March 17, 2025, https://www.mass.gov/how-to/apply-to-the-cool-corridors-grant-program; Cool Corridor Design Toolkit, City of Tampa, Florida, 2024, https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5dba154a6b94a433b56a2b1d/t/67914a8234bd0b67d5d2e863/1737575063765/Tampa_Cool+Corridor+Concept_Cool+Corridor+Toolkit_FINAL.pdf; “Strickland Tackles Extreme Heat and Modernizes Transit Corridors,” Marilyn Strickland, accessed October 13, 2025, https://strickland.house.gov/2025/07/15/strickland-tackles-extreme-heat-and-modernizes-transit-corridors/; “Cooling Montgomery County’s corridors,” A Montgomery Planning Department Blog, accessed October 13, 2025, https://montgomeryplanning.org/blog-design/2025/04/cooling-montgomery-countys-corridors/; “Cool Corridors Action Guide,” Vibrant Cities Lab, accessed October 13, 2025, https://www.vibrantcitieslab.com/heat-and-mobility/.; “Cool Corridors,” Engage Bridgeport, accessed October 13, 2025, https://engage.bridgeportct.gov/coolcorridors; “Cooling corridors study,” Metro, accessed October 13, 2025, https://www.oregonmetro.gov/tools-partners/grants-and-resources/cooling-corridors-study.

7. “A City of Green Possibilities,” Singapore Green Plan 2030, accessed October 16, 2025, https://www.greenplan.gov.sg/; “Tokyo Green Biz – Green Urban Development,” Tokyo Metropolitan Government, January 1, 2024, https://www.english.metro.tokyo.lg.jp/w/000-101-000551; “Green Infrastructure,” European Commission, accessed March 17, 2025, https://environment.ec.europa.eu/topics/nature-and-biodiversity/green-infrastructure_en; “Cities100: Medellín’s interconnected green corridors,” C40, October 2019, https://www.c40knowledgehub.org/s/article/Cities100-Medellin-s-interconnected-green-corridors?language=en_US.

8. “Nature-based Solutions,” IUCN, accessed March 17, 2025, https://iucn.org/our-work/nature-based-solutions.

9. “Nature Based Solutions for Cooling,” Cool Coalition, accessed March 17, 2025, https://coolcoalition.org/about/what-we-do/nature-based-solutions-for-cooling/; Prashant Kumar et al., “Urban heat mitigation by green and blue infrastructure: Drivers, effectiveness, and future needs,” The Innovation 5, no. 2 (March 4, 2024): 100588, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xinn.2024.100588; Radhika Sundaresan and Namitha Nayak, “Building Climate-Resilient Cities with Nature-Based Solutions,” WELL Labs, September 27, 2024, https://welllabs.org/building-climate-resilient-cities-with-nature-based-solutions/; Bidisha Banerjee, Sandhya Basu, and Lokesh Kumar, “Chapter 10 – Green space and mental well-being research in India: An urgent need for intervention,” Impact of Climate Change on Social and Mental Well-Being (2024): 147-201, https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-443-23788-1.00010-5; Jyothi S. Menon and Richa Sharma, “Nature-Based Solutions for Co-mitigation of Air Pollution and Urban Heat in Indian Cities,” Frontiers in Sustainable Cities 3 (2021), https://doi.org/10.3389/frsc.2021.705185.

10. Passive Cooling Strategies for Sustainable Buildings, Ozone Cell, Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change, Government of India, 2024, https://ozonecell.nic.in/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/5-Passive-Cooling-Strategies-for-Sustainable-Buildings.pdf.

11. Cool Roofs Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs), NRDC, 2020, https://www.nrdc.org/sites/default/files/india-cool-roofs-faq-20200527.pdf; Madan, “Telangana Announces a Groundbreaking Cool Roof Policy,” 2023; Jaykumar Joshi et al., “Climate change and 2030 cooling demand in Ahmedabad, India: opportunities for expansion of renewable energy and cool roofs,” Mitigation and Adaptation Strategies for Global Change 27, no. 44 (2022), https://doi.org/10.1007/s11027-022-10019-4; Primer for Cool Cities: Reducing Excessive Urban Heat – With a Focus on Passive Measures, Energy Sector Management Assistance Program (ESMAP), 2020, https://www.esmap.org/primer-for-cool-citiesreducing-excessive-urban-heat.

12. Passive Cooling Strategies for Sustainable Buildings, 2024; Primer for Cool Cities, 2020.

13. Neil Singh Bedi et al., “The Role of Cooling Centers in Protecting Vulnerable Individuals from Extreme Heat,” Epidemiology 33, no. 5 (2022): 611-615, https://doi.org/10.1097/EDE.0000000000001503; “Cooling Centers Guidance,” Commonwealth of Massachusetts, accessed March 17, 2025, https://www.mass.gov/info-details/cooling-centers-guidance; “Mist cooling system at Raipur stn provides respite from high temp,” Times of India, May 4, 2024, https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/raipur/mist-cooling-system-at-raipur-station-provides-relief-from-high-temperatures/articleshow/109829066.cms; “Mist cooling system at Nagpur railway station brings relief to passengers in sweltering heat,” ThePrint, May 28, 2024, https://theprint.in/india/mist-cooling-system-at-nagpur-railway-station-brings-relief-to-passengers-in-sweltering-heat/2105797/; Robert D. Meade et al., “A critical review of the effectiveness of electric fans as a personal cooling intervention in hot weather and heatwaves,” The Lancet Planetary Health 8, no. 4 (2024): E256-E269, https://doi.org/10.1016/S2542-5196(24)00030-5; Kamala Thiagarajan, “As temperatures in India break records, ancient terracotta air coolers are helping fight extreme heat,” BBC, May 31, 2024, https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20240530-how-ancient-knowledge-of-terracotta-is-cooling-modern-indian-buildings; “Heat Action Plan: ‘Cool Bus Stop’ launched at Lal Darwaja,” Indian Express, March 19, 2025, https://indianexpress.com/article/cities/ahmedabad/heat-action-plan-cool-bus-stop-launched-at-lal-darwaja-9893567/.

14. “Cool Roofs, Hot Cities: Insights from Field Evidence and Real-World Application,” Lodha Group, June 25, 2025, https://www.lodhagroup.com/blogs/sustainability/cool-roof-benefits-government-policies-challenges; “Heat Action Plan: ‘Cool Bus Stop’ launched at Lal Darwaja,” Indian Express, March 19, 2025, https://indianexpress.com/article/cities/ahmedabad/heat-action-plan-cool-bus-stop-launched-at-lal-darwaja-9893567/.

15. “Cities100: Medellín’s interconnected green corridors,” C40, last modified October 2019, https://www.c40knowledgehub.org/s/article/Cities100-Medellin-s-interconnected-green-corridors?language=en_US.

16. Jon Creyts, “Dispatch from Mumbai: Experiencing the Urban Gem of Palava,” RMI, last modified December 19, 2023, https://rmi.org/dispatch-from-mumbai-experiencing-the-urban-gem-of-palava/.

17. “Tackling Urban Heat: Palava City’s Efforts to Aid India’s Battle with Heat,” Lodha Group, last modified August 5, 2025, https://blogs.palava.in/palava-city-tackling-urban-heat-by-sustainable-development/.

18. Our first step in identifying potential sites involved estimating land surface temperatures (LST) from satellite sources using an internally developed GIS model for rapid LST mapping with minimal inputs. The analysis used high-resolution Landsat 8-9 data available from the USGS Earth Explorer. Although LST does not directly measure ambient temperatures felt by humans, it serves as a useful proxy. After pinpointing candidate locations based on elevated LST, we identified neighbourhood road infrastructure (such as local and collector roads) that could be leveraged to support community heat resilience.