Proceedings of the Round table Discussion.

Establishing a Whole-Building Embodied Carbon Baseline and Benchmark for Residential Buildings in India

The Claridges, New Delhi

On November 24, 2025, RMI India Foundation, in partnership with the Building Materials and Technology Promotion Council (BMTPC) and the Lodha Foundation, convened a roundtable of experts to advance the development of embodied carbon baselines and benchmarks for India’s residential building sector. The event brought together researchers, practitioners, policymakers, industry associations, and real estate developers to review emerging findings, propose methodologies, validate technical approaches, and identify pathways to establish a national-level embodied carbon baseline and benchmark.

Key discussion themes included a sampling framework and statistical approach, the scope boundary for life cycle assessment, the physical scope boundary, materials classification, the area normalisation metric, and the embodied carbon coefficient cascade.

Context

India’s rapid urbanisation presents a critical opportunity to transform building design and construction practices. With a large share of the upcoming building stock expected to be urban residential, embodied carbon (EC) emissions from this sector are projected to nearly double by 2050. As millions of new housing units are planned and built across the country, establishing EC baselines and benchmarks becomes essential to guide low-carbon material choices, support evidence-based policymaking, and accelerate decarbonisation of the built environment.

The roundtable has been organised with the intent to establish a Whole-Building Embodied Carbon Baseline and Benchmark for India’s residential sector. This effort is piloting a Whole-Building Life Cycle Assessment methodology, supported by a sampling framework that accounts for key variations across seismic zones, construction technologies, and building heights. A statistical approach will convert results from selected buildings into a nationally representative baseline and benchmark, yielding credible, data-driven EC insights for residential buildings nationwide.

Overview of Participation

The roundtable brought together 16 participants from 14 organisations, representing research, practice, policy, industry associations, and development, to exchange emerging findings and build collective momentum towards developing national-level EC baselines and benchmarks.

Dr Shailesh Agrawal (Executive Director, BMTPC) highlighted shifting priorities in India’s housing sector. While the Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs continues to drive rapid construction under Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana (PMAY) 2.0, the programme is increasingly integrating priorities such as thermal comfort and green housing, aligning with BMTPC’s current focus. He noted that attention to EC is growing, but it still receives far less focus than operational carbon.

Dr Agrawal observed that structural barriers, including low public awareness, continued reliance on conventional materials in owner-driven housing, and limited translation of research innovations into large-scale deployment, are slowing progress toward sustainability. He called for a national platform to support informed low-carbon material choices for builders and homeowners, and emphasised the need to move beyond simplistic embodied-carbon estimation by incorporating clear benchmarks and thresholds into government tenders. He concluded by underscoring that India’s diverse construction technologies and existing data gaps are major hurdles, and addressing these gaps is essential for scaling initiatives.

Tarun Garg (Principal, RMI India Foundation) further underscored the importance of establishing credible EC baselines and benchmarks for the Indian residential sector. He emphasised that collective and collaborative technical validation is essential to ensure methodological robustness for a national-scale benchmarking exercise, noting that shared expertise will be crucial in shaping an actionable pathway for sectoral transformation. He also proposed that RMI India Foundation will continue to host further convenings as progress advances on this important subject.

Key Discussion

The discussion on establishing national-level embodied carbon baselines and benchmarks for residential buildings focused on a typology-based sampling framework. Participants highlighted the importance of accounting for variations in seismic conditions, building heights, and construction typologies across the country. The conversation also drew on whole-building life-cycle assessment (WBLCA) results from a PMAY affordable housing project in Gujarat, using it as an illustrative example to explore how a comprehensive physical scope and assessment approach can enable meaningful comparisons across different residential project types. The proposed methodology by RMI India Foundation is anchored in five technical pillars:

- Sampling framework and statistical approach

- Life cycle assessment scope boundary

- Physical scope boundary and materials classification

- Area normalisation metric

- EC coefficient hierarchy

Together, these elements establish a structured foundation for developing robust whole-building embodied-carbon baselines at a national scale. Key insights and takeaways from these discussions are summarised below:

1. Sampling Framework and Statistical Approach

Proposal: The sampling framework aims to capture variation in EC across India’s residential building stock by stratifying samples around four key variables: 1) Construction technology: monolithic concrete, reinforced cement concrete-frame (RCC), load-bearing masonry; 2) Seismic zone (Zone II, III, IV, V, VI); 3) Building height: low-, mid-, and high-rise; 4) Residential typology: multi-family housing. In this phase, two typologies have been evaluated: high-rise monolithic concrete buildings (G+25–G+40) and mid-rise RCC-frame buildings (G+14). Low-rise RCC-frame buildings (G+3/4) will be assessed next.

Discussion:

- Sample size for statistically robust baselines

The current sampling matrix is considered comprehensive, and it is suggested that the scope be expanded to include confined masonry, another predominant typology. A statistically significant sample size should be determined for each seismic zone, building typology, and height band to ensure that variations are accurately reflected in the baseline. - Seismic zone considerations

The seismic zone has a direct and substantial influence on structural quantities and, therefore, on the EC footprint, compared to the climatic zone. It must remain a core stratification variable for national-level baseline development. - Structural variation and data sources

Structural engineers maintain detailed, reliable quantity datasets across large project portfolios, and their involvement can significantly improve the accuracy and speed of material-quantity aggregation.

2. Life Cycle Assessment Scope Boundary: A1–A3 vs A1–A5

Proposal: The proposed LCA boundary for EC baselining is currently defined as A1–A3 (product stage, i.e., A1 – Raw material supply; A2 – Transport to manufacturing; A3 – Manufacturing). During the assessment phase, two boundary conditions were tested: one project was evaluated for A1–A5 (product + construction stage), and the other for A1–A3 (product stage). However, it was difficult to obtain data for stage A4 (transport to site) and A5 (construction/installation processes). Therefore, A1–A3 is recommended as the standard boundary condition for establishing EC baselines in the current phase. A4 and A5 data will be captured where reliable information becomes available as data sources mature.

Discussion:

- A1–A3 (cradle-to-gate): A1–A3 should be adopted as the initial scope for embodied-carbon baselining because the product stage accounts for the largest share of embodied emissions in most buildings, and data availability is strongest. Data for A1–A3 is the most consistently available from manufacturers and bill of quantities (BOQs), enabling scalability without requiring major behavioural changes from stakeholders.

- A1–A5 combined (cradle-to-site, including construction): While A4–A5 are important for a comprehensive cradle-to-site assessment, they cannot be made mandatory at this stage due to high variability in transport and logistics and challenges in capturing construction-site energy-use data. When A5 data is reported, only emissions attributable to material use, not the entire construction process, should be included. Collecting A4 and A5 data, where possible, will be valuable for future benchmarking.

- Reporting individual A-stages (granular cradle-to-gate): Disaggregated reporting of A1, A2, A3, A4, and A5 enables more precise identification of hotspots across extraction, transport and manufacturing. Once a sufficiently large dataset is built, granular reporting will improve material-level insights and support more targeted decarbonisation interventions.

- A1–A5 + C-stages (full life cycle)

C1–C4 (demolition, waste transport, processing, and disposal) are recognised as important for circular-economy and material-reuse considerations, but data availability is limited. Modelling end-of-life stages depends on uncertain future parameters, such as service life and recovery rates, making them impractical for early-phase baselining.

3. Physical Scope Boundary and Materials Classification

Proposal: The proposed classification follows the OmniClass classification system to organise building components for the WBLCA embodied carbon. The scope of assessment was constrained to building elements, including the substructure comprising foundations, subgrade enclosures, slabs-on-grade, and the shell, consisting of the superstructure, exterior walls, cladding, roofing, and vertical and horizontal enclosures. Interior construction, including partitions, doors, and windows, is included in the assessment, while Interior finishes are excluded.

Discussion:

- Structural envelope scope: The baseline should include substructure, superstructure, and the external envelope, as these components represent the core load-bearing and high-emission elements of a building. Internal partitions should be excluded because their volumes vary significantly across unit layouts (e.g., 1BHK vs. 4BHK), thereby distorting comparisons across benchmarks.

- Material consideration: High-impact materials (such as concrete, cement, steel, and walling materials) should be prioritised as they drive the majority of embodied emissions (up to 70%–80%). Although a typical BOQ contains 30–40 line items, typically 8–10 materials account for most emissions; focusing on these ensures accuracy without additional complexity.

- Interior finishes: Flooring, tiling and other interior finishes can be excluded at this stage due to high variability in market segment, developer positioning, and resident preference, and segment differentiation. Interior layers contribute relatively less to total EC compared to structural materials in early lifecycle stages.

4. Area Normalisation Metric

Proposal: The proposed normalisation metric is the total constructed area, measured to the outer face of exterior walls and excluding shafts and infrastructure at the site. It includes all constructed spaces (including terraces, machine rooms, mumty areas, refuge zones, overhead and underground water tanks, basements, and façade elements, etc.) and shared on-site amenities.

Discussion:

- Built-up area (BUA): Built-Up Area is the simplest and the most consistently reported metric across projects. The metric works well for baselining because developers already report it, avoiding definitional ambiguities around balconies, corridors, wall thickness, and other grey areas. It is preferred due to low reporting friction and high compatibility with tender documents, BIS (Bureau of Indian Standards) formats, and RERA (Real Estate Regulatory Authority) submissions.

- BUA including parking and shared amenities: If structural materials are included in embodied-carbon quantification, then all shared amenities and constructed footprints (excluding infrastructure) must be included in the area denominator to maintain consistency and ensure that the baseline reflects the true scale of construction.

- Carpet area/gross floor area/gross internal floor area

Carpet Area has analytical value but is not suitable as the primary normalisation metric for initial baseline development. GFA (Gross Floor Area) and GIFA (Gross Internal Floor Area) are typically used internationally (e.g., CLF — Carbon Leadership Forum; ILFI — International Living Future Institute), but are inconsistently interpreted across regions, especially regarding the treatment of balconies, terraces, and shared spaces, making them unsuitable for early-phase baselining.

5. Embodied Carbon Coefficient Hierarchy

Proposal: The proposed coefficient-selection methodology establishes a hierarchical cascade to guide the consistent use of embodied-carbon emission factors. The framework prioritises India-specific and product-specific data to ensure maximum relevance, beginning with the latest manufacturer-, factory-, and product-level coefficients, followed by India-specific product-level industry averages where manufacturer data is unavailable. Older India-specific datasets may then be used in the same order of preference to avoid data gaps. International datasets are used only as a last resort, starting with the latest industry-average values that can be localised to Indian conditions wherever feasible, and finally with the latest non-India product-specific values.

Discussion:

- Data consideration

Projects should use the best available data rather than waiting for perfect datasets, which would delay assessments. Product-level EPDs (Environmental Product Declarations) are the preferred first choice; third-party-verified LCAs (Life-Cycle Assessments) are valid alternatives when EPDs are not available and should not be disregarded. Existing datasets (e.g., Ecoinvent, CLF, and International Organization for Standardization’s datasets) should be used when no product- or industry-level data are available and must be clearly labelled in reporting. - Identifying materials with high variation vs low variation: Materials with high variation in environmental performance (e.g., bricks and blocks) require a product-specific coefficient to avoid skewed results. Materials with low variation across markets (e.g., reinforcement steel) can rely on sector- or industry-average emission factors. Databases that include regional identifiers strengthen accuracy without significantly increasing data-collection burden. Existing market directories and databases can serve as a practical starting point for embodied-carbon coefficients.

- Importance of transparency for comparability: All embodied-carbon values must clearly declare whether they originate from product-level data, industry-average datasets, or default protocols. Different calculation methodologies must not be mixed without disclosure (e.g., TRACI 2.1 vs. TRACI 2.2), as doing so undermines comparability.

Conclusion

Experts emphasised the need for statistically robust sampling frameworks to ensure credibility and scalability of EC baseline assessments and benchmarks for India. With the sector expanding rapidly, whole-building baselines and benchmarks are essential to guide low-carbon material choices and support evidence-based policy. The methodology advances a diversified typology-based sampling strategy, prioritises life cycle stages A1 to A3, focuses on high-impact structural materials, normalises results to built-up area, and uses a hierarchical approach for coefficient selection. These form a practical foundation for national benchmarking. Although data gaps remain, the group emphasised that assessment should begin now, with refinements incorporated as the methodology matures. Sustained collaboration across researchers, developers, policymakers, and industry stakeholders will be essential for implementation, and RMI India Foundation will continue engaging partners to refine the methodology and build alignment.

Appendix

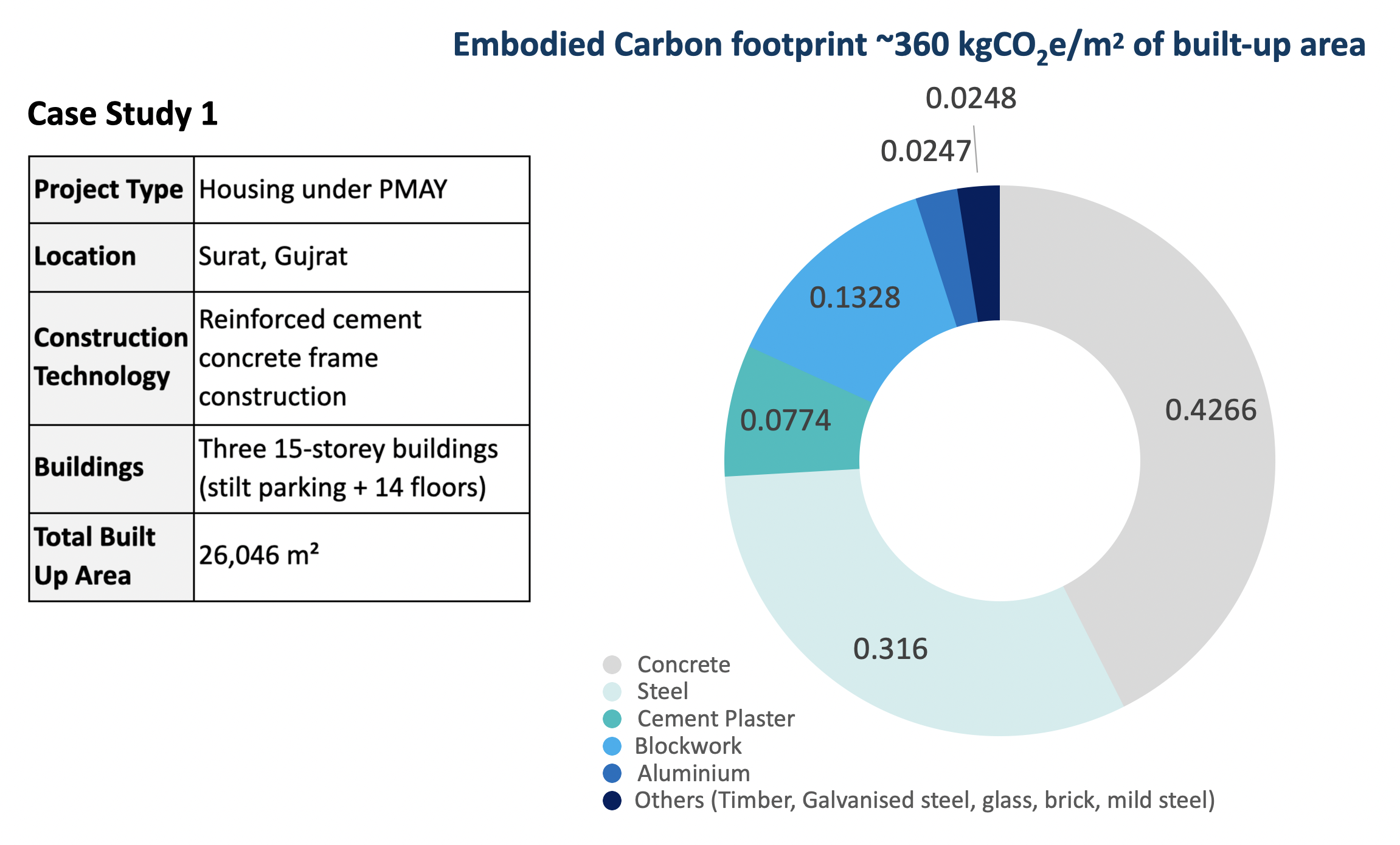

Case Study 1

| Project Type: | : Housing under PMAY |

| Location: | : Surat, Gujarat |

| Construction Technology: | : Reinforced cement concrete frame construction |

| Buildings: | : Three 15-storey buildings (stilt parking + 14 floors) |

| Total Built Up Area: | : 26,046 m² |

Exhibit 1: Embodied Carbon Intensity ~360 kgCO2e/m2 of Built-Up Area

RMI India Foundation Graphic. Source: Authors’ analysis

RMI India Foundation Graphic. Source: Authors’ analysis

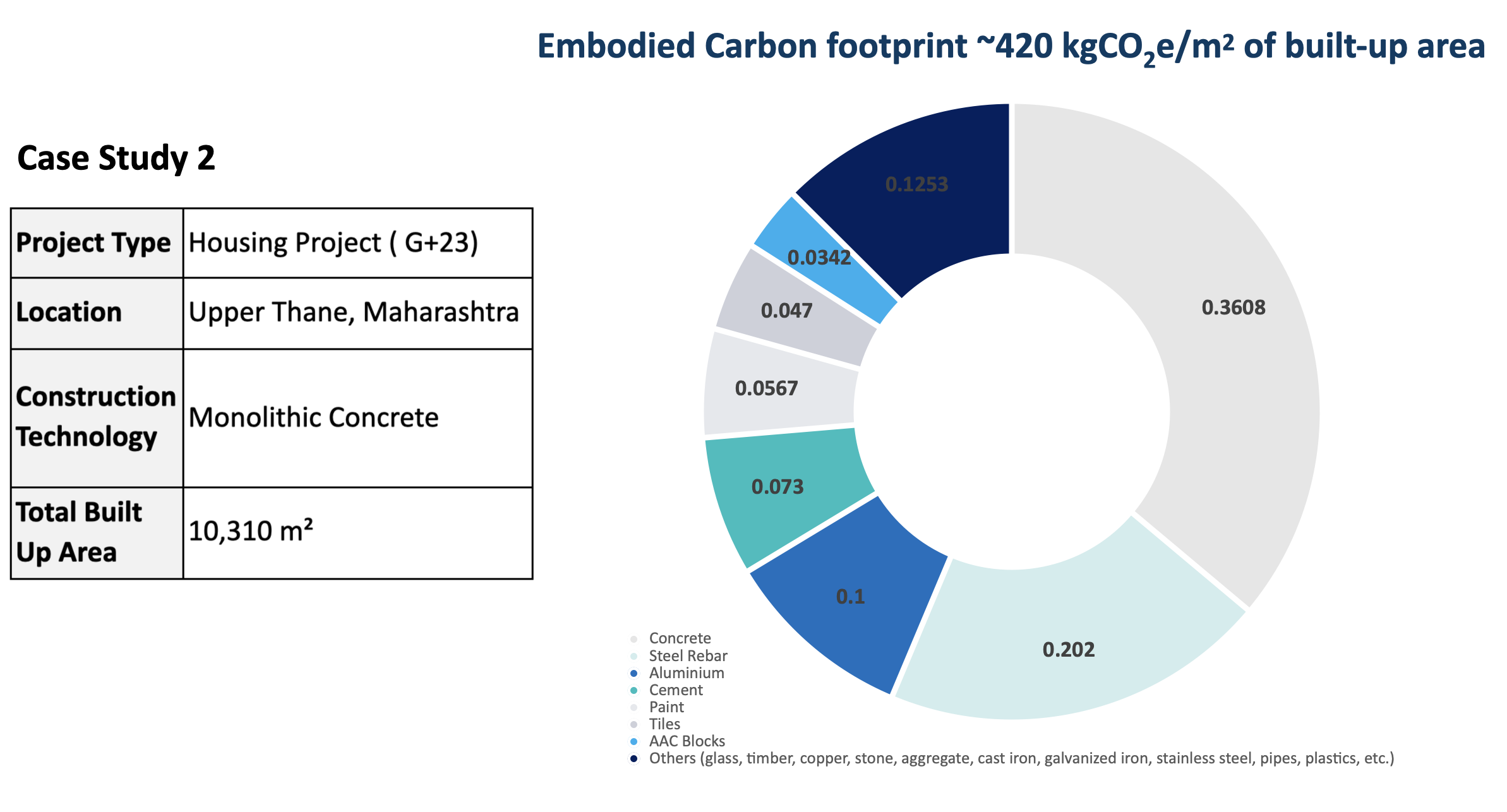

Case Study 2

| Project Type: | : Housing |

| Location: | : Mumbai, Maharashtra |

| Construction Technology: | : Monolithic Concrete Technology |

| Total Built Up Area: | : 10,310 m² |

Exhibit 2: Embodied Carbon Intensity ~420 kgCO2e/m2 of Built-Up Area

RMI India Foundation Graphic. Source: Embodied carbon in high-rise buildings, Lodha, RMI India Foundation,2022, https://www.lodhagroup.com/blogs/sustainability/embodied-carbon-in-high-rise-buildings-insights-from-a-baselining-study.

RMI India Foundation Graphic. Source: Embodied carbon in high-rise buildings, Lodha, RMI India Foundation,2022, https://www.lodhagroup.com/blogs/sustainability/embodied-carbon-in-high-rise-buildings-insights-from-a-baselining-study.

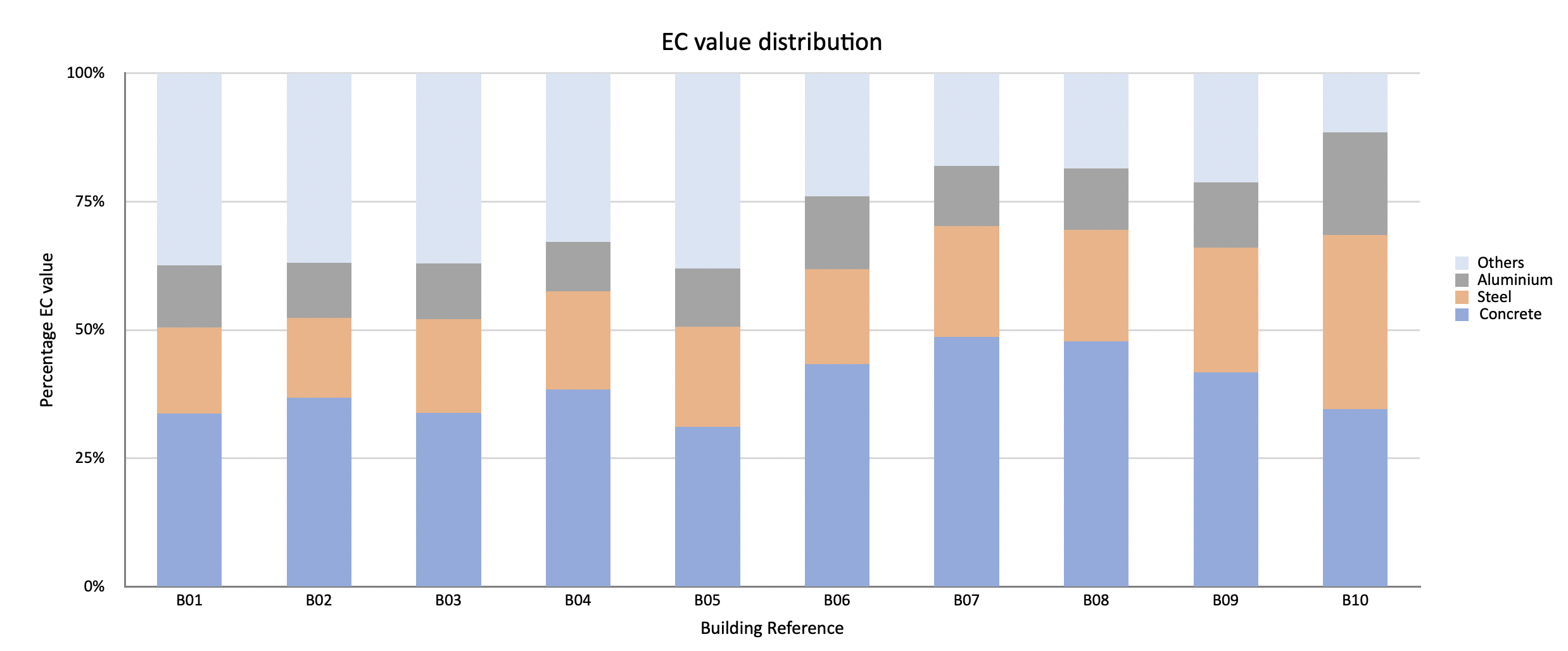

Case Study 3

| Project Type | : Housing |

| Location | : Maharashtra |

| Construction Technology | : Monolithic Concrete Technology |

| Buildings | : 10 buildings |

Exhibit 3: Embodied Carbon Intensity ~350-550 kgCO2e/m2 of Built-Up Area

| Building Reference | Building EC (KgCO2e/m2) | Configuration | Building Height (m) | Built-up Area(m2) |

| B01 | 352 | G+10 | 32 | 8026 |

| B02 | 394 | G+14 | 44 | 16989 |

| B03 | 391 | G+18 | 56 | 15984 |

| B04 | 444 | G+23 | 70 | 10424 |

| B05 | 376 | G+23 | 70 | 10490 |

| B06 | 477 | G+35 | 121 | 32150 |

| B07 | 528 | G+39 | 122 | 34617 |

| B08 | 518 | G+40 | 123 | 43965 |

| B09 | 502 | G+40 | 130 | 29091 |

| B10 | 567 | 2B+G+40 | 136 | 127830 |

RMI India Foundation Graphic. Source: Baselining Embodied Carbon in Building Sector, Lodha, 2025, https://www.lodhagroup.com/blogs/sustainability/baselining-embodied-carbon-in-building-sector.

Exhibit 4: Embodied carbon footprint of core construction materials

RMI India Foundation Graphic.

Source: Baselining Embodied Carbon in Building Sector, Lodha, 2025, https://www.lodhagroup.com/blogs/sustainability/baselining-embodied-carbon-in-building-sector.